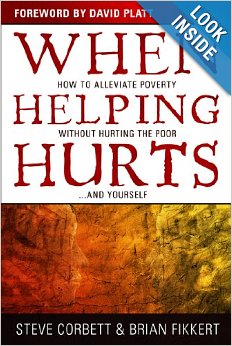

While preparing for a work project in Guatemala to establish a health and water cooperative in conjunction with New DenverChurch www.newdenver.org, I wanted some perspective on the most effective practices for providing assistance in developing countries. My concern is that in spite of the lengthy war on poverty waged in the United States since the 60’s, and billions of dollars of foreign aid ($2.3 trillion spent by Western nations since World War II to be more precise) that sustainable progress in relieving poverty continues to be elusive since nearly 40% of the world’s population still lives on two dollars per day and the U.S. poverty rate is stuck at 12%. Corbyn Small a friend who works with Plant with Purpose www.plantwithpurpose.org recommended that I read “When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty without Hurting the Poor and Yourself” by Steve Corbett and Brian Fikkert.

While preparing for a work project in Guatemala to establish a health and water cooperative in conjunction with New DenverChurch www.newdenver.org, I wanted some perspective on the most effective practices for providing assistance in developing countries. My concern is that in spite of the lengthy war on poverty waged in the United States since the 60’s, and billions of dollars of foreign aid ($2.3 trillion spent by Western nations since World War II to be more precise) that sustainable progress in relieving poverty continues to be elusive since nearly 40% of the world’s population still lives on two dollars per day and the U.S. poverty rate is stuck at 12%. Corbyn Small a friend who works with Plant with Purpose www.plantwithpurpose.org recommended that I read “When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty without Hurting the Poor and Yourself” by Steve Corbett and Brian Fikkert.

Intention Does Not Equal Effectiveness

But first, a little closer to home, do you, like I do, wrestle with ambivalence when passing a homeless person looking for a handout? No more. Based on my reading and conversations with people regularly working to relieve poverty of various types, my new perspective suggests that although handing the person a couple dollars alleviates my guilt and satisfies his current need, it has the potential to cause long term damage to me and the person I am “helping.” Well-intentioned but misdirected service can corrupt our understanding of the roots of poverty and exacerbate the very conditions it intends to cure.

Bad Definitions Drive Poor Solutions

I was surprised to discover that a number of the principles for poverty alleviation parallel those necessary for leading organizational change. As with any leadership initiative, the initial challenge is to properly define the issue, in this case the problem is poverty. If poverty is determined to be a lack of material things, then the response should be to give people enough stuff until they are no longer poor. If poverty includes deficiencies in other areas such as purpose, hope and relationships, then the response will appear much different. For example, consider a person seeking money to pay a past due electric bill. The simple solution is to provide the funds to pay the bill. However, failing to determine and address the reason for the need masks the underlying issues. Depending whether the money that could have been used to pay the bill was used to buy lottery tickets or to pay for a child’s medical bills suggests different types of financial management training which will be of greater long term value. In addition, enabling the person to establish a financial foundation to meet his own needs removes the shame associated with perpetually asking for assistance and eliminates the unhealthy inferior-superior relationship that develops between the giver and the receiver.

The Complexity of Difficult Problems

Leaders who attempt to resolve intractable systemic problems quickly learn how inter-related everything is. You pull one loose thread in the corporate fabric and it seems to unravel the whole thing. “When Helping Hurts” asserts that it is the dysfunction in relationships that creates poverty rather the simple absence of material possessions. They identify four relationships which can be impoverished; with God, with self, with others and with creation. In essence, we need to be in meaningful relationships with others to get the things we need – food, shelter, education and love, and to contribute the gifts that we have – skills, knowledge, work and compassion. Paradoxically, this wider net ensnares many of us. Materially wealthy individuals have sacrificed relationships with friends and family to achieve their success. Those in positions of power can develop a “god-complex” believing they are superior to those over whom they have influence.

The leadership lesson here is that if we don’t listen, we don’t learn. And we tend not to listen to those who we assume are of lower status. And we assume others are lessor when we measure them by a single dimension – money, title, power. As a result, we miss the richness of cultural, emotional and relational diversity.

Redefining Objectives

As excellent leaders do, when the typical solutions fail, they go back the assumptions and redefine the problem in order to develop fuller and more creative solutions. In poverty alleviation work, interventions are categorized by whether the situation requires relief, rehabilitation or development. The key is to apply the appropriate intervention after evaluating the circumstances. Don’t keep providing relief (short-term aid) after the crisis has past when development (long-term programs) is called for.

Typical Mistakes

The major mistakes in poverty alleviation are no different than in any cultural transformation effort. They are:

- Failing to involve the affected people in all aspects of the process; which leads to:

- Misdiagnosing the problem; which leads to:

- A limited or ineffective range of solutions; which leads to:

- Using the wrong strategy for the particular situation; which leads to:

- Limited or unsustainable improvement.

And these mistakes stem from those in charge mistakenly believing that because they are in the position of influence or are materially advantaged they are wiser than everyone else combined. Instead, success in organizational and community transformation arises from the messy yet empowering process of including the affected people in every phase – from defining the problem to assessing the available resources to initiating new ways of thinking, working or living.

Solution-oriented Processes

Poverty alleviation experts employ a principle for utilizing the resources of the community known as asset-based community development (ABCD) in which all people involved are prompted to contribute their skills, knowledge, relationships and money towards the development efforts in order to create ownership and sustainability. Asset mapping is used to build a data base of all the available resources of the individuals, businesses and organizations in the community, thereby exposing an array of assets to apply to the presenting issues. Appreciative Inquiry (AI) examines the positive aspects of the community’s past and then outlines a story which demonstrates how this history and the qualities it reveals can be used to design a better future. AI moves from dialogue (what should be) to delivery (what is working or has worked) to discovery (what gives life) to dream (what are we called to do).

Leaders of any organizational, community or cultural transformation would be wise to contemplate the lessons of this important work.

Where have you made incorrect assumptions about the cause of a problem and as a result initiated solutions that have failed or made a situation worse?

Follow

Follow